The conventional wisdom in 2013 about obstetrics is that C-sections are “bad.” This conventional wisdom is not shared by most obstetricians, but it has spread to academia where conferences are held on how to decrease the C-section rate to some theoretical ideal. Earlier this week I wrote about a new study in the policy journal Health Affairs. That paper was deeply misleading and ignored important data. Now comes another C-section study that sets out to show that C-sections have unacceptable risks, but actually demonstrates the opposite. Moreover, the study suffers from a serious flaw, which if remedied would lower the purported risks even further still.

The study is Consequences of a Primary Elective Cesarean Delivery Across the Reproductive Life by Miller, Hahn and Grobman. The goal of the study is admirable and important:

There is a paucity of data regarding the reasons a woman may request a primary cesarean delivery. Fear of childbirth and its associated morbidity have been cited as prominent contributing factors toward such a request. These concerns have been supported by some experts, who have suggested that a planned cesarean delivery is less morbid than a trial of labor when weighing in the rates of an unplanned cesarean delivery…

One of the limitations of the available data is its focus on short-term outcomes related only to the initial pregnancy. However, the decision about route of delivery in one pregnancy has ramifications through subsequent pregnancies given the increased morbidity associated with multiple abdominal surgeries and uterine scars. Yet the comparative morbidity across multiple pregnancies related to the initial approach to delivery remains uncertain. A properly powered observational study that would provide such data would require many thousands of women given the relatively low frequency of adverse events that occur with either delivery approach. The logistic difficulty of this makes such an observational study unlikely to be performed. Thus, we designed a decision analysis to provide a framework for understanding the risks over the reproductive lifespan associated with either trial of labor or elective cesarean delivery for an initial delivery.

So far so good. The authors want to find out the risks of a maternal request C-section across the subsequent reproductive lifespan. It’s too hard to do an actual study of what the risks really are, so they plan to create a theoretical model to estimate them. Now comes the serious problem: there is no data on the risks of maternal request C-sections, so they plan to use elective C-sections as a proxy for maternal request C-section. But in the medical context, elective does NOT mean unindicated, it means non-emergent. So many “elective” C-sections are performed for medical reasons in no way represent unindicated C-sections. The authors show some awareness of this problem:

This model included women at term with a singleton gestation in the vertex presentation and no contraindication (eg, placenta previa) to a trial of labor.

In other words, the model took into account absolute contraindications to vaginal delivery, but not other indications for “elective” C-sections. Therefore, the results are likely to dramatically overstate the risks of a maternal request C-section.

Nonetheless, the findings are remarkable for just how safe C-sections have become. Moreover, the authors did not repeat the dreadful mistake of the Health Affairs piece and did include some neonatal outcomes making it possible to compare the risks of C-sections to the risks of vaginal delivery.

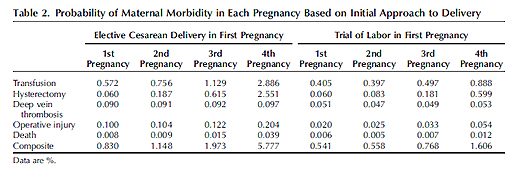

Let’s look at maternal morbidity first, which is summarized in the table below.

What jumps out at me is just how low the risks really are. The death rate for a non-emergent primary C-section is 8/100,000 as compared to a death rate for vaginal delivery of 6/100,000, for a difference of only 2/100,000. And that difference is likely to be a dramatic overestimate in the case of a truly elective (vs. non-emergent) C-section.

It is true that the risk rises with ever subsequent C-section. For the 4th C-section, the death rate is 39/100,000 as compared to 12/100,000 for a 4th vaginal delivery, for a difference of 27/100,000. Once again this is likely to be a vast overestimate. In addition, 85% of American women have fewer than 4 children, so this difference applies to a small subset of women.

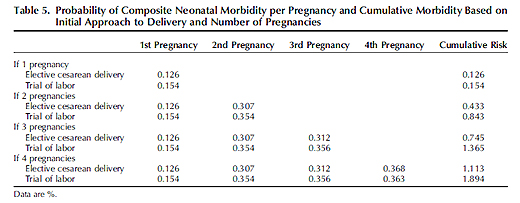

Now let’s look at the outcomes for babies, which can be found in the table below.

In contrast to the results for mothers, the authors unfathomably chose to ignore the neonatal death rate, surely the single most important piece of data in evaluating neonatal outcomes. They chose to restrict neonatal outcomes to cerebral palsy and brachial plexus injuries. C-section results in a neurologic injury rate for a first C-sections is 12.6/1000 as compared to 15.4/1000 demonstrating that C-section has a protective effect for babies. Although the protective effect disappears by the 4th C-section, the difference is only 5/100,000.

The omission of neonatal death rates is inexcusable. It’s not as if that information is unavailable. Although, to my knowledge, no study has been done to specifically look at the differences in neonatal mortality as the number of C-sections rise, there are studies that demonstrate that C-section is protective, such as Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality After Elective Cesarean Delivery by Signore and Klebanoff that showed that if 1 million women underwent C-section at 39 weeks instead of waiting for onset of labor and attempting vaginal delivery, 692 more babies would be saved, 517 cases of intracranial hemorrhage and 377 brachial plexus injuries would be prevented.

Even in the absence of mortality data, the authors acknowledge that C-sections are protective:

…this model demonstrates that elective first cesarean delivery may allow one to avoid the infrequent intrapartum neonatal events that occur during trials of labor and that may be associated with longterm neurodevelopmental impairment…

Neonatal outcomes chosen included those known to be affected by route of delivery. Insofar as elective cesarean delivery is often scheduled at 39 weeks of gestation, some have suggested that stillbirth rates could be reduced by using a strategy of elective cesarean delivery. Elective cesarean delivery at 39 weeks at gestation would, indeed, reduce the incremental increase in stillbirth associated with expectant management of pregnancy after this point…

The authors conclude:

… Our analysis cannot determine that one approach is “better” than another, particularly because some outcomes (eg, incontinence) remain poorly characterized and because such a determination would need to include preferences accorded to different routes of delivery by women. Nevertheless, this analysis can provide information that may be helpful in counseling and emphasizes that although an initial cesarean delivery may result in only a marginally increased risk of maternal morbidity and a marginally decreased neonatal risk compared with a trial of labor, the difference in maternal morbidity throughout reproductive life become increasingly larger, whereas the difference in perinatal outcomes becomes increasingly smaller.

The bottom line is that even multiple C-sections may have modest risks and for women planning only one or two children, the benefits of elective C-section may actually outweigh the risks.