This tracing shows a baby in serious trouble.

Surprised? You might be if you thought that a fetal heart rate tracing supplied the same information as intermittent ausculation (listening) with a doppler. But electronic fetal monitoring provides a wealth of information that cannot be obtained by listening, and that allows for a more comprehensive view of fetal well being.

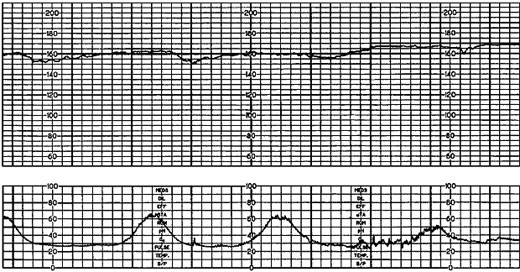

What information does this tracing provide? To understand, you need to know what we are looking at. We are looking at two different graphs created simultaneously by the fetal monitor. The top graph shows the fetal heart rate; the bottom graph shows the uterine contractions. The information in the top graph can only be understood in relation to the information in the bottom graph.

Let’s start with the basics:

* The baseline fetal heart rate is approximately 160 beats per minute. This is a normal fetal heart rate. Therefore, if you were listening briefly at most points during which this tracing were created, you would think that the baby was doing fine.

* There is decreased variability. We know from looking at millions of tracings that the normal fetal heart rate will created a jagged line. This is known as “variability.” As the circulatory needs of the fetus change from moment to moment, the heart rate adjusts from moment to moment. When the baby’s brain is deprived of oxygen, the heart rate will lose variability, and the line will look smoother. This heart rate tracing has lost its variability; this baby is in trouble.

There is no way to determine variability while listening, so intermittent auscultation would not alert you to this ominous development.

* There are no accelerations. A well oxygenated baby will move from time to time. That will be reflected in temporary increases in the heart rate (accelerations) lasting for fractions of a minute or more. Without a written tracing, it is difficult to determine if there are accelerations.

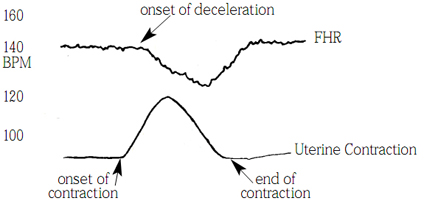

* There are subtle late decelerations. A deceleration is a brief decrease in heart rate. Their significance is not in how deep they are, but in where they are located in relation to the contraction. They are categorized as early (before a contraction), variable (at the peak of a contraction), or late (staring during a contraction but continuing after the contraction has ended).

The following illustration provides a clearer view of a late deceleration. Notice how the decrease in heart rate starts during the contraction and continues after the contraction has ended:

Late decelerations are an indication that the baby is not getting enough oxygen through the placenta to “hold its breath” during a contraction when the supply of oxygen is temporarily cut off. Repetitive late decelerations are an unequivocal sign of fetal distress.

It is important to note that the depth of the deceleration has nothing to do with the severity of oxygen deprivation. Subtle late decelerations, such as those in the tracing at the top, are nonetheless extremely ominous.

Can you hear a late deceleration with intermittent monitoring? That depends entirely on when you listen, how long you listen, and whether there are contractions during time when you are listening. The subtle late decelerations in the tracing above might be very difficult to appreciate by listening alone. That’s because the heart rate changes only by 5-10 beats per minute and only for a period of 15-20 seconds.

Notice what you don’t see:

You don’t see a bradycardia, a sustained period of abnormally low heart rate. That’s because bradycardia is often a terminal event. Most babies can tolerate long periods of significant oxygen deprivation before they die, and they may not have any bradycardias until immediately before death. On this tracing, there is never a single moment when the heart rate is outside of the normal range, but the baby is nonetheless suffering from serious oxygen deprivation.

This is almost certainly what is happening in hours before a dead baby drops into a homebirth midwife’s hands. The midwife may be intermittently listening to the baby’s heart rate, but unless she is listening for long enough AND frequently enough AND exactly at the right times AND can distinguish subtle changes in heart rate, she will be blissfully unaware that a baby is dying right in front of her.

Homebirth advocates and their midwives who insist that the baby’s heart rate was “fine” until just before delivery are completely wrong. The baby’s heart rate was not fine; they just couldn’t tell what was happening because they only listened intermittently.

Homebirth advocates and their midwives who insist that no one could have predicted that the baby would need an expert resuscitation are completely wrong. The baby was not fine; they simply couldn’t tell one way or the other.

Homebirth advocates and midwives who insist that the same thing would have happened at the hospital are completely wrong. The pattern would have been picked up, probably hours before the baby’s death, and a C-section would have been done. The baby would have been born healthy and screaming and the mother and midwife would have been fuming about the “unnecessary” C-section.

Homebirth advocates and midwives who insist that intermittent monitoring is just as safe as electronic monitoring are completely wrong. If you can’t pick up subtle changes in heart rate, you can’t diagnose and treat fetal distress early, before the baby’s brain has been permanently damaged.

Look at the tracing above again. Ask yourself:

Could you (or anyone) hear that heart rate pattern?

If not, then you can understand how very easy it is to listen intermittently to a “normal” heart rate, and then unexpectedly have a dead baby drop into your hands.