People put a lot of trust in Consumer Reports, but reading their piece about C-section rates suggests that such trust may be misplaced.

While some C-sections may not be absolutely necessary for the health of the mother or baby, there is no scientific evidence that the C-section rate is either a safety metric, or an accurate quality metric. Indeed, ranking hospitals by C-section rate provides no information of value. But Consumer Reports, which has fallen down the rabbit hole of natural childbirth, just like The New York Times, seems not to have noticed that the C-section rate reflects procedures, not outcomes. Most mothers are interested in the OUTCOME of childbirth, a healthy mother and a healthy baby. In a blindingly obvious misstep, Consumer Reports doesn’t even bother to mention, let alone investigate outcomes, which would be reflected in mortality and morbidity rates, NOT C-section rates.

What Consumer Reports does not want you to know about C-sections is that the C-section rate has nothing to do with either safety and little to do with quality.

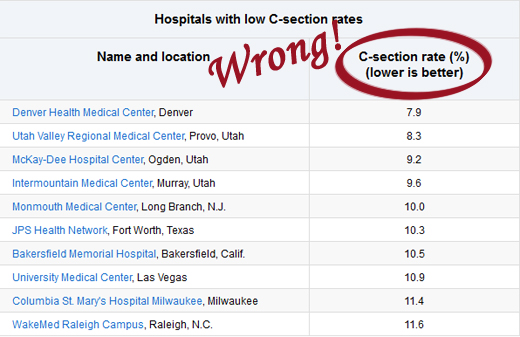

The primary problem with the Consumer Reports’ piece is reflected in their graphics:

The fundamental assumption, on which the entire piece rests, is that a lower C-section rate is better. That is 100% FALSE. There is simply no scientific evidence to support the claim.

For better or for worse, there is no consistent relationship between C-section rates and outcomes. While that may mean that higher C-section rates are not better, it ALSO means that lower C-section rates aren’t better, either. Why? Because the ideal C-section rate is the one where all women and babies who NEED a C-section get one, and not too many women and babies who don’t need a C-section end up with one anyway. Notice that I did not say that there would be NO unnecessary C-sections. Given the current state of technology that can only imperfectly tell us in advance which C-sections are necessary, it is better to do many unnecessary C-sections in order not to miss any necessary ones.

How do we know that a lower C-section rate is not better? Consider international C-section rates. The countries with the lowest C-section rates in the world are those with the highest perinatal and maternal mortality. That’s because lack of access to C-sections leads to preventable perinatal and maternal deaths.

But how about countries where C-sections are easily available? As the chart below (adapted from Cesarean Section Rates and Maternal and Neonatal Mortality in Low-, Medium-, and High-Income Countries: An Ecological Study) demonstrates, there is no discernible relationship between C-section rates and safety:

Italy, the country with the highest C-section rates has one of the best safety profiles.

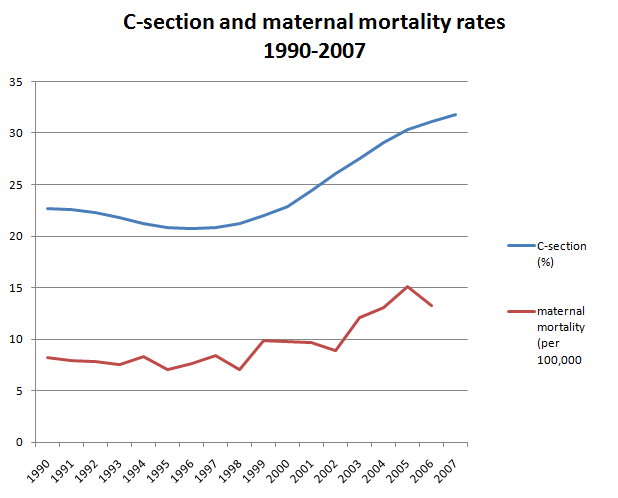

Consider the impact of C-section rates on safety over time in this country. What about an association between the rising C-section rate and rising maternal mortality? A graph comparing the maternal mortality rate and the C-section rate shows a correlation.

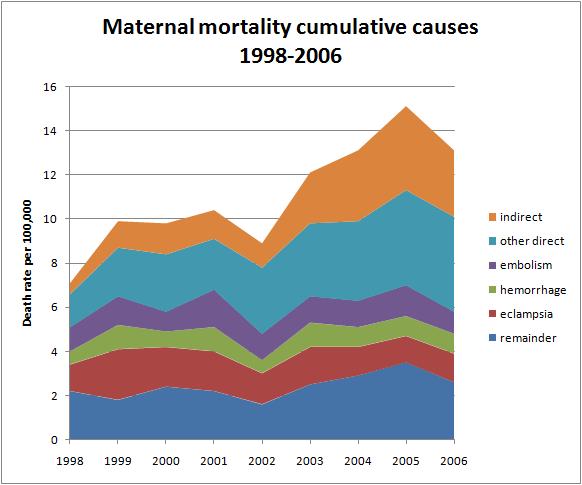

But correlation is not causation. If the rising C-section rate were leading to an increased maternal mortality rate, we would expect to see C-section complications, such as hemorrhage and embolism increasing disproportionately. But that’s not what we see. As the following graph makes clear, both hemorrhage and embolism death rates did not change their contributions to overall maternal mortality.

In addition to being based on a completely false empirical assumption, the CR piece also suffers from bias. Consider the title: What hospitals don’t want you to know about C-sections. The inescapable impression is that hospitals are hiding their C-section rates and that CR had to go to extreme lengths to obtain those rates. Yet C-section rates are widely available for free on public website. And as far as individual hospitals are concerned, Consumer Reports was easily able to obtain C-section rates for 1,500 hospitals in 22 states. That doesn’t sound like hospitals “don’t want you to know.”

Ultimately, though, the piece reflects the bias of the natural childbirth philosophy that privileges process over outcome. Consumer Reports is so sure that vaginal delivery is “better” than C-section that they never even bothered to check the outcomes at the various hospitals. But the philosophy of natural childbirth is NOT based on scientific evidence (it was dreamed up by Grantly Dick-Read, a eugenicist who was trying to convince women of the “better classes” to have more children than their “inferior” counterparts) and is both perverse and dysfunctional. It is a form of biological essentialism, judging women on the function of their reproductive organs as opposed to their intellect or character. It assumes that women are improved by agonizing pain and that they value the experience of a baby transiting the vagina more than whether the baby actually survives the transit. Natural childbirth is anti-feminist in the extreme, and is not safer, healthier, better or superior to childbirth with any and all interventions.

Consumer Reports is flat out wrong in pretending that C-section rates are a safety metric and they are wrong to encourage women to judge either hospitals or doctors based on C-section rates. They owe their readers an apology and an investigation of real safety metrics, so women can choose hospitals based on quality.

Consumer Reports tries to destroy trust in hospitals and obstetricians (not coincidentally the same objective of natural childbirth advocates and organizations) and replace it with trust in their Consumer Reports itself. Based on this irresponsible piece, they are not worthy of that trust.