We have a terrible problem in contemporary scientific research. Or it would be more accurate to say we have two terrible problems.

First, a great deal of published research is junk, generally because of spurious statistical analysis.

Second, the media credulously publishes any press release, the more irresponsible the better.

[pullquote align=”right” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]It doesn’t matter what the paper showed because the results are NOT statistically significant.[/pullquote]

Consider this story in STATNews, usually a reliable outlet for medical news. Entitled Babies’ face scans detect exposure to low amounts of alcohol in utero, it is remarkably injudicious. Why? Because by the authors’ own admission, their results AREN’T statistically significant.

Here’s a simple explanation of statistical significance:

When a statistic is significant, it simply means that you are very sure that the statistic is reliable.

So when results aren’t statistically significant, it means that the results are NOT reliable. In other words, the paper does NOT show what it claims to show.

STATNews reported:

…[C]an a small amount of drinking by an expectant mother show itself on her child’s face?

To answer that question, researchers in Australia analyzed three-dimensional images of over 400 children’s faces and heads around their first birthday. An algorithm … looked for any substantial deviations from a standardized template made from all of the children’s scans. The children’s mothers also answered surveys about their alcohol intake several times before giving birth — data that researchers used to separate them out into groups based on when and how much they drank…

So far, so good.

3-D facial scanning picked up some differences … It also picked up on one otherwise difficult-to-measure change called mid-facial hypoplasia, in which the center of the face develops more slowly than the eyes, forehead, and lower jaw. Perhaps most notably, there seemed to be slight differences in the mid-face and at the tip of nose even in the children of women who had only had a little to drink and only in the first trimester of their pregnancy. (However, almost no overall changes were statistically significant.)

The fact that the overall results weren’t statistically significant is not a minor issue that merits only a comment in parentheses. It is the most important thing about the study. In truth, the authors’ data shows that tiny amounts of alcohol do NOT affect a baby’s face. The people at STATNews should never have repeated the claim and certainly not titled their article based based on the erroneous claim.

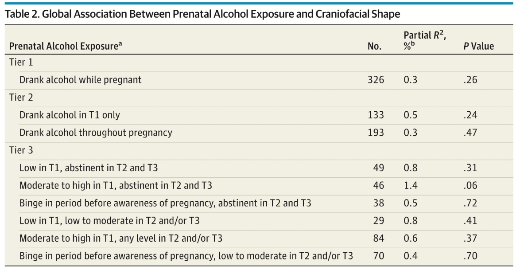

No matter how they sliced and diced the data (by level of drinking or by trimester), the results are not statistically significant.

It’s notoriously difficult to get negative results published. Perhaps this is why the authors kept slicing and dicing. They came up with this:

The authors looked at whether the results sliced on the basis of how a mother FELT after drinking. Did she feel the effects of alcohol as usual or more quickly than usual? When the mother reported feeling the effects of alcohol as usual, there was still no difference in facial structure based on alcohol exposure. But when the mothers reported feeling the effects of alcohol more quickly than usual, two out of nine variables were statistically significant.

In what way is the mothers’ perception of alcohol effects relevant? I can’t think of any plausible reason to analyze the data that way besides p-hacking, aka data dredging.

What is p-hacking?

Data dredging (also data fishing, data snooping, and p-hacking) is the use of data mining to uncover patterns in data that can be presented as statistically significant, without first devising a specific hypothesis as to the underlying causality.

The process of data dredging involves automatically testing huge numbers of hypotheses about a single data set by exhaustively searching — perhaps for combinations of variables that might show a correlation, and perhaps for groups of cases or observations that show differences in their mean or in their breakdown by some other variable.

P-hacking occurs in a desperate effort to find something, anything, that is statistically significant in the data. If you engage in p-hacking you will almost always find something that is statistically significant because tests of statistical significance produce some false positives by definition.

When large numbers of tests are performed, some produce false results … hence 5% of randomly chosen hypotheses turn out to be significant at the 5% level, 1% turn out to be significant at the 1% significance level, and so on, by chance alone.

P-hacking leads to testing hypotheses suggested by the data and that is invalid:

If one looks long enough and in enough different places, eventually data can be found to support any hypothesis. Yet, these positive data do not by themselves constitute evidence that the hypothesis is correct. The negative test data that were thrown out are just as important, because they give one an idea of how common the positive results are compared to chance. Running an experiment, seeing a pattern in the data, proposing a hypothesis from that pattern, then using the same experimental data as evidence for the new hypothesis is extremely suspect, because data from all other experiments, completed or potential, has essentially been “thrown out” by choosing to look only at the experiments that suggested the new hypothesis in the first place.

When interviewing the mothers, the authors presumably asked a variety of questions. Then they apparently exhaustively searched for combinations of variables that might show statistical significance. When they found a few variables that were statistically significant if they sliced the data based on mothers’ perception of alcohol effect, they created a new hypothesis — even small amounts of alcohol affect the facial structure of children so long as the mothers feel the effects of alcohol sooner than they expected —- and use the data that generated the new hypothesis to “prove” the new hypothesis.

In other words, instead of acknowledging these few results, though statistically significant, are meaningless, the authors blithely ignore what they are required to take into account and brazenly conclude:

The results of this study suggest that even low levels of alcohol consumption can influence craniofacial development of the fetus and confirm that the first trimester is a critical period.

The truth is that their results confirm the EXACT OPPOSITE; there is no evidence that alcohol ingestion had any impact on facial structure no matter how desperately the authors wish to claim it.

The folks at STATNews should have understood that and should have debunked the paper, not compounded the problem of junk science by repeating the spurious claims.